4.3 Practical Approaches to Wine & Food Pairing

|

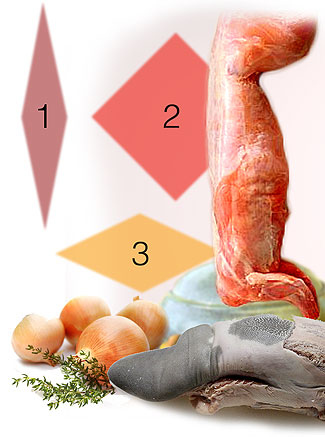

| Above: Symbols for the three major meal types and some of the ingredients for rabbit & ox tongue sausage. But which wine will match the dish? After identifying the three basic meal types, we go on to identify the key ingredients, preparation techniques and the key flavours these elements give rise to. Only then can the fine tuning begin in order arrive at the most suitable wine to pair with the selected dish. |

Identifying the Ingredients: 1. Meal Types.

Confronted by a complex global gastronomy that includes cuisines with no tradition of wine production, it is helpful to isolate three major meal types before considering a wine and food match. Doing so we become aware of the limitations and demands each meal type involves. Here they're represented by three simple symbols[pictured right]as follows:

Classical Western cuisine culminates in France with a style that can best be described as 'Haut Cuisine' [pronounced oat kwee-ZEEN] - denoting a level of technique brought to bear on food and its preparation resulting in complex, refined, elegant dishes. (1) This is the objective of many of the world's great chefs at top restaurants and hotels. It is based around perfect harmony and balance being achieved, with the right weight of wine and food being consumed over a reasonable period. Unlike the agrarian style meal there are more courses, each graduated in lightness at either side of a peak - hors d'oeuvres or canapes, a light clear soup, entre, main course, cheese and greens, sweets, petites-fours and perhaps an intermediate number of sorbets, with the climax being the main course. The quality and complexity of the dishes invites different wine pairings for each course. Typically, younger, simpler wines are served earlier in the meal followed by the oldest, more subtle wines. Usually, the better the wine is, the plainer the food preparation, so as to allow the nuances of the wine to be fully experienced without being masked by intense food flavours. Haut Cuisine remains the classic entertainment 'dinner party' model and for many people the most familiar context in which they'll endeavour to create superior wine and food harmonies.

2. Regional / Agrarian

These meals are represented by a long, but fat, squat diamond configuration signifying a small number of heavy to very heavy dishes such as those found in the traditional fare of German, Austrian and English cuisine. The ingredients themselves are rather limited offering little culinary challenge, often dictated by what could be grown in cold climates or difficult terrains. Goulash, kransky, stews and shepherds pie may be hearty, tasty and generally nutritious, however, they cannot claim to be complex and would typically be combined with beer, simple, robust wines or even a spirit. They're work-horse meals for hard working people, reflecting a cultural achievement of societies backbone.

3. Fast Food

The squashed diamond symbolising the fast food meal indicates instant gratification and satiation within one course, sometimes followed by a sweet. Insofar as it's possible to create a complexity of flavours with minimal ingredients, fast foods rarely attempt to do so - they're not designed to be savored and as such, represent a drastic shift from when people looked forward to their meals at home, eating with their families and at a leisurely pace. By contrast, fast food relies on a quick preparation according to standardized processes, the results of which neither offend nor excite the majority. Rather than the pursuit of flavour, its common characteristics are limited to the primary instinctive tastes - sweet, salty and umami (more recently, spiciness and texture have been added to the formula). The result of decades of advances in food marketing and food science, a billion dollar-a-year business devoted to inventing new additives and ingredients, fast foods are accepted by indifferent palates as normal and even nutritious. One might think these factors would make it antithetical to anything as complex as wine, but this is not necessarily the case.

The three meal models are not mutually exclusive. Fine Chinese cuisine, for example, is a variation on French Haut Cuisine. It's a banquet style meal with many small courses, all in balance and eaten over a longer period of time. It remains equally concerned with harmony and building complexity towards its zenith, progressing to the end of the meal through a series of lighter courses. Sandwiches, pasties etc. are all variations of the fast food meal while 'Bistro style' eating is usually a Mediterranean variation on the agrarian meal. A single course is sometimes followed by a dessert. Obviously an extended 'haut cuisine' style meal will have quite different wine requirements than a pizza or stew.

|

|

|

| Winter, 1573 oil on canvas. | Vertumnus, Roman God of the seasons, c.1590-1 | Autumn, 1573, oil on canvas. |

Identifying the Ingredients: 2. The influence of Meal Preparation.

By continuing from the general to the more specific, our next consideration is the manner in which a particular dish has been prepared. The most fundamental role of food preparation, regardless of meal type, is to ensure that the size, hardness and texture of the food require approximately the same level of force to break apart and chew. Any food that requires excessive chewing makes for an unpleasurable experience. The appearance of a meal is also of fundamental importance as it signals the anticipation of culinary pleasure or displeasure. Then of course, come cooking techniques. These are extraordinarily varied and in some respects, can be categorised in a similar fashion to wine making in its delivery of three different 'grades' of flavour - primary, secondary & tertiary.

Secondary flavours are introduced by a chef from the preparation, cooking method and time taken to cook the food. While a wine maker's influence can include the use of various types of yeasts, fermentation techniques, oak barrels, maturation times amongst other variables, a chef has an even broader scope for modification via the use of herbs, spices, stock reductions, complex sauces and marinating techniques. Although, a skilled chef or winemaker prefer to enhance the primary characteristics of a dish rather than swamp them. The chef also has the ability to alter the texture of an ingredient, its consistency, moisture content, oiliness, hardness and of course the temperature that the dish is finally served at, which also impacts upon final flavour.

Then finally there are the tertiary flavours which develop over time. Time is occasionally generous to food flavour, allowing a prolonged infusion process to occur, or like wine, a food can be kept too long, when it starts to break up and decompose.*

Food preparation techniquestake four basic forms which sometimes overlap:Raw, Heat Modified, Air Dried or Preserved. Associated with these techniques are processing procedures which can dramatically modify a food's flavour and texture (consider for a moment how char grilling will impact upon the final flavour of a meat as opposed to steaming, and so on).

2. Heat modified foods include any food to which some form of heat has been applied to break down its chemical structure and make it more digestible. Procedures include steaming, boiling, poaching, pressure cooking, frying, stir frying, deep frying, grilling and various 'dry heat' methods such as toasting, smoking and roasting via pot, spit, oven, barbeque, flame, etc. The latter procedures in particular, result in the deep rich flavours of browned meats and caramelized vegetables whereas steaming or poaching etc generally results in more lightly flavoured fare.

3. Air dried involves dehydration. Essentially the structure of the food is broken down with minimal human intervention, usually via sun drying. In this category one would also include food which has been buried and allowed to dry and break down in the soil. Freeze drying is not dissimilar to air drying in that it removes the water content of the food and allows it to be added back at a later date.

4. Preserved foods have been modified into a more durable (and sometimes more delicious form) by salting, curing, spicing or pickling. Preserved foods cover all categories including fruits, vegetables, grains, eggs, animals and fish. Preserving is achieved in combination with mediums and substances such as vinegar, salt, sugar or alcohol (in its various distilled and fermented forms). Meat and game can be cured in a dry cellar.

What should have become clear is that in the equation of wine and food, wine tends to remain unchangeable while food remains inherently flexible. It is easier to change the character of a dish than the personality of a wine. For this reason simple or extravagant dishes are frequently designed around the wines being served, rather than vice-versa. The sommelier or wine master at a Wine & Food Society will usually select the menu in consultation with the chef. They discuss the ingredients and preparation procedures in order to develop a profile of dominant flavours which they then attempt to match with wines. 'Dry runs' might be held prior to an important dinner, the various combinations tested and modified where necessary. Some find the matching process easier by considering wine itself as a food - in this way its flavour components are visualised in the same way as ingredients in a dish. This makes some sense since by either approach, the objective match can be achieved by breaking down both the food and wine into three sensory categories:

2. Texture - also known as 'mouthfeel'

3. Flavours

2. Texture or Mouthfeel of both wine and food relate to the dominant mouthfeel and tactile sensations, rather than any perceptible tastes. Textures are relatively easy to identify, and like basic tastes and flavours they can be used to provide similarity or contrast in matchings. In wine, the most familiar tactile sensation is probably that of 'astringency' derived from grape and oak barrel tannin phenols. (5) Also of significance is the 'body' of a wine (also known as 'weight') which increases with higher concentrations of tannin and alcohol. It is the correspondence between the body or weight of a wine and the weight or richness of the food that probably accounts for the origins of the "red wine with meat and white wine with fish rule." However, the range of mouthfeel sensations in both wine and food is considerably more varied. Everyday mouthfeel experiences include the fizzy tingle of CO2 in carbonated drinks, the burn from hot peppers and spices such as ginger and cumin, alkaloids, fats and oils, as well as tactile sensations of pain, temperature and electricity. All of these sensations can be experienced in various parts of the mouth, augmenting the overall sensation of 'flavour'. (See 1.3 Taste Categories: Myths & Modern Research for a more thorough account of mouthfeel.)

3. Flavour is not, as some would lead us to believe, simply another expression of aroma. Rather, because the nose shares an airway (the pharynx), with the mouth, we smell and taste our food simultaneously giving rise to flavours. Therefore flavour is more accurately described as the summation of smell and taste. The complex and dual nature of flavours means they reside at the top of the wine and food matching hierarchy. Yet while flavour elements will often represent the final consideration once the basic taste components and texture of the food have been determined, they are not necessarily the most important considerations in a wine and food match.

| A Simple Experiment with Wine & Food Bruce Zoecklein from the Dept. of Food Science & Technology, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, suggests the following experiments to demonstrate the interactions between sweet, salt, acid and astringent sensations as they are perceived in various combinations and their potential impact on wine flavour: Exercise 1 illustrates sugar and acid interaction. * Taste any wine and focus on the perception of acidity. * Taste a strongly acidic food, such as lemon juice. * Allow your palate to adjust for a moment, then re-taste the wine. * After the lemon juice, the wine tastes much sweeter which is the same as saying less acidic. The composition of the wine didn't change, but the perception did. * Taste the wine again, noting the perception of sweetness. * Taste some sugar and re-taste the wine. After the sugar, the wine tastes much less sweet or more acidic. Exercise 2 helps to demonstrate how foods can influence astringency and bitterness features. * Taste a red wine or heavily oaked white and note the astringency, if present. * Taste a source of protein or fat such as butter and re-taste the wine. * The wine will taste less astringent and/or bitter, perhaps even a little sweet, although the change is not as dramatic as noted with sugar and acid. Proteins and fats have the ability to bind with tannins, thus muting the sense of astringency and bitterness. * The perception of sweetness is enhanced proportionally to the reduction in astringency and bitterness. Exercise 3 illustrates there is a relationship between high salt content in foods and the perception of acidity and astringency in wines. * Select two wines, a young astringent red and a high-acid white wine. * Taste the red wine and focus on the perception of astringency. * Taste some salt and re-taste the red. * Rough tannins in reds can be magnified by salt, although minor salt concentrations in foods are not usually a problem. * Taste the high acid white wine and note the perception of acidity. * Taste the salt and re-taste the wine. The salt frequently magnifies the perception of acidity. (5) |

3. A Practical Exercise in Wine & Food Matching

Bearing in mind the two basic ways by which wines and foods are successfully matched - similarities or contrasts (see Chapter 4.2) - we'll now work through a practical example based upon the varietals, Pinot Noir and Shiraz. For the purpose of this exercise I have confined the process to the principle aromas / flavours and the most frequent and most important secondary aromas / flavours of these wines. As wines change with time, so will the importance of some of the characteristics, but the principles will remain the same.(Note: Due to the vast number of wines available on the market which can vary significantly from vintage to vintage in their quality, dominant aroma and flavour, in order to select the right one for your course may require trial and error or consultation with a wine merchant).

Pinot Noir has a number of primary aromas / flavours - their importance can be listed as follows:

2. . game

3. . cherry

4. . spice

5. . decaying flesh / manure

6. . raspberry

7. . ribeena

8. . stalky

Shirazhas a number of primary aromas / flavours - their importance can be listed as follows:

2. . blackberry

3. . spice

4. . plums

5. . stewed fruit

6. . vanilla

7. . chocolate

8. . leathery

We now proceed to find a dish with primary aromas and basic components that will be harmonious and compliment those of the grape variety. I have selected a recipe from Gail Thomas's book"A Cooks Guide to Australia's Gourmet Resources"(6),Rabbit and Ox Tongue Sausage. Although we've never cooked this before, we assume that the person who created the recipe has and is reasonably satisfied with the balance of flavours. It is also assumed that you're sourcing fresh, quality ingredients.

(Note: The full method for cooking this recipe can be found online. See "Gourmet Cooking & Wine" and scroll down the page to find the section under 'rabbit).

The first step in the pairing process is to consider the elements of the recipe which are as follows:

1 Fresh Ox Tongue

1 Onion finely chopped

1 Sprig Thyme

1 Egg beaten

Salt and Pepper to taste

The Stock:

1 Onion chopped

1 Carrot sliced

1 Stalk Celery chopped

1 Sprig each of Thyme, Parsley, Marjoram

1 tspn Salt

750ml White Wine

Sauce Stock:

Bones and carcasses of the rabbits

1 Onion chopped

1 Carrot sliced

1 Stalk Celery chopped

Sprig Parsley

50gm Butter

For Sauce:

100ml Cream

1-2 tablespoons Grain Mustard

First let us list the dominant aromas, tastes, flavours of the ingredients in order of importance.

2. . Rabbit

3. . Onion

4. . Thyme

5. . White Wine

Secondly the dominant aromas, tastes and flavours of the sauce.

2. . . Cream

3. . . Stock

Both Pinot Noir and Shiraz have a number of harmonious aspects and certainly the blackpepper, spice, stewed fruit and leathery qualities of the Shiraz could be an attractive composition in harmony with the ox tongue. Now the fine tuning will begin. (Remember, this is all a learning process and even mistakes help build one's memory library for future occasions).

In this case, we've decided to use the Pinot Noir as the match.

In the recipe a white wine is suggested for the cooking of the stock - this will mean that the rabbit and ox tongue will have been infused with much of the white wine's flavour, and it also presents itself as an opportunity to serve the wine with the finished meal. Rabbit and ox tongue are fairly strongly flavoured meats, and ox tongue has a 'sweetness' about it that almost presupposes the white wine to be a ripe unwooded Chardonnay. This wine displays ripe peaches and melon aromas and flavours with some nutty overtones that will complement the dominant meat flavours. It also has the acidity to cut across both the fat in the tongue and the cream sauce. Why not use Sauvignon Blanc or Semillon as the stock wine? The reason being that it is too herbaceous and would conflict with the tongue and rabbit. At first the choice of a Chardonnay, or even a white wine may seem unusual with a sausage dish, where a Pinot would have been seemed the immediate choice, however,the Pinot would not have the acidity to cut across the sauce. We may either change the sauce or continue with serving the chardonnay with the complete dish. Another reason for not using a Pinot in the stock is aesthetic - it would discolour the pale rabbit meat and fresh tongue, so affecting the meal's visual appeal.

Wines Styles & Foods for Special Consideration

Sweet Wines

Count Lur Saluces of the famous Sauternes producer Chatteau d'Yquem, one of the world's greatest sweet wines, once said drinking his family's wine with a dessert is a"disaster." It should be consumed with Rocquefort cheese, foie gras or even roast chicken, he said, but never with a dessert. The reason is that desserts can often have a sugar content greater than 20% while sweet wines are seldom greater than 10%. Very sweet foods often over-balance the perception of a wine's sweetness, making the wine taste thin and somewhat acidic or sour. This is the same sensory response suggested in the basic taste experiments above: if you taste sugar and then wine, the wine will taste considerably less sweet. Wine historian Hugh Johnson agrees, writing about Sauternes,"The Anglo Saxon world drinks it as the richest of endings to a rich meal although it can easily be swamped by too sweet a dessert. It deserves a far more appreciative following."(7)Put simply, for those uninitiated in Sauternes, the versatility of these wines should not be underestimated. An entire three course meal can easily be created around Sauternes wines alone, with the results being some of the most exciting wine and food matching sensations one is likely to experience. Apart from classic dessert combinations like creme caramel, freshly cracked walnuts, fruit pies, fruit salads and soft fruits (apricots, peaches, pears and berries have their sweetness modified by their native acid content making them suitable matches), one wouldn't think of many more adventurous alternatives unless you visited the Sauternes itself and spent some time with the locals. On one trip to the region, I dined at the Auberge du Vin Sauternes, where the only food being served was duck, barbequed on the dry canes of Sauternes vines and served with a plate of frits (McDonald's-type thin slices of fried potato). The wine was 1983 Chateau Guiraud Sauternes. The combination - sensational. On another occasion, again in Bordeaux, but this time at the pickers lunch at Chateau Petrus, rough barbeque lamb chops which had been marinated in Sauternes were produced for the hungry pickers; again the combination was wonderful. Other combinations which may come as a surprise include ewes milk cheese, a quiche or black pudding and apples(boudin aiy pomsies) or pan fried trout. However, perhaps the most surprising match, and a favourite of Comte Lur Saluces, owner of Chateau d'Yquem, is crayfish and Sauternes. The combination is nothing short of sublime. Should any of the above ingredients be unavailable or simply beyond budget, Australian chef and food writer, Gail Thomas, has a simple, inexpensive alternative."I've found when we've served d'Yquem, usually put with foie gras, blue cheese, lobster and fresh pear, which are supposedly the 'matches' , the pear wins out every time".(8)

Chocolate

One of the clashes that is repeatedly made is the pairing a botrytis style dessert wine with chocolate. Intuitively, one might expect sweet similarities in the two components to harmonise, but the subtle bitterness of the chocolate completely swamps the ripe fruit in the wine. Conversely, try a chocolate cake with a glass of good champagne, and the acid of the champagne works with the cocoa of the chocolate. A rich Sparkling Shiraz or a Pedro Ximenez Sherry also results in success. Still better, try dark chocolate desserts with Bual or Malmsey Madeira. Madeira's combination of acidity and sweetness harmonises extremely well. Rich, full bodied Highland Single Malt Scotch Whiskies will also accompany dark chocolate, such as those made by theDalmoreorGlenfarclasdistilleries. Gail Thomas adds,"With chocolate, it's often said that the higher the alcohol the better the match so grappa also tends to work well".

Wine & Cheese

Contrary to popular belief, cheeses are probably the most difficult foods to pair with table wines. The gluey, tongue coating texture of cheese means it can smother the basic taste sensations making wine seem one-dimensional. Bernice Madrigal-Galan and Hildegarde Heymann of the University of California, Davis, presented trained wine tasters with cheap and expensive versions of four different varieties of wine. The tasters evaluated the strength of various flavours and aromas in each wine both alone and when preceded by eight different cheeses. They found that cheese suppressed just about everything, including berry and oak flavours, sourness and astringency. Only a butter aroma was enhanced by cheese. Heymann conjectured that the reason for this might be because cheese itself contains the molecule responsible for a buttery 'wine aroma'. The results of the study suggested that strong cheeses suppressed flavours more than milder cheeses, but flavours of all wines sampled were suppressed by cheese.(9)

There are exceptions. Cheeses with high acid levels such as Chevre (goat's cheese) work well with a wine of similarly high acidity, such as Sancerre (Sauvignon Blanc). Stilton is a traditional accompaniment to quality Port, and as has been mentioned, Blue vein cheeses or Roquefort remain the classic dairy match for botrytis affected wines. It should be noted that the type of bread used with the cheese adds yet another dimension. For further reading, Will Studd's book "Cheese Slices" has a chapter devoted to this subject.(10)

For more unusual and exciting recipes see "Gourmet Cooking & Wine".

In this free online cook book, Gail Thomas [right], one of the most creative and innovative chefs and food writers in Australia, presents well developed Australian recipes which Vintage Direct matches with appropriate wines. We also thank Gail for reviewing Vintage School's chapters on wine and food and for offering her suggestions.

Footnotes & Bibliography

* One story is told about a young English chef who was instructed to hang and supervise some pheasants for a period. Being rather inexperienced, he allowed them to hang a little too long, however to no apparent loss of flavour. In fact, once served, the guests relished the strong gamey flavours sending their compliments back to the chef adding that they had never enjoyed risotto quite as much. The unsuspecting guests had actually been delighting in the flavour of roast maggots.

1. The Elements of Cooking. Michael Ruhlman. Black Inc. Books, 2007. Melbourne, Australia

2. Red Wine with Fish: The New Art of Matching Wine with Food by David Rosengarten, Joshua Wesson. Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group, November 1989

3. Matching Table Wines with Foods. Bruce Zoecklein. Dept. of Food Science & Technology, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

4. Red Wine with Fish: The New Art of Matching Wine with Food by David Rosengarten, Joshua Wesson. Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group, November 1989

5. Matching Table Wines with Foods. Bruce Zoecklein. Dept. of Food Science & Technology, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Note: Astringency is probably more accurately described as a chemically induced tactile sensation, rather than a purely tactile one.

6. A Cooks Guide to Australia's Gourmet Resources. Gail Thomas. 1989.

7. Guidelines for Successful Food & Wine Pairings. Randy Kemner. The Wine Country.

8. Gail Thomas is a freelance wine and food writer based in Geelong, Victoria, Australia.

9. Vintage or Vile, Wine is all the same after cheese. New Scientist Magazine issue 2535. 19th Jan 2006

10. Cheese Slices by Will Studd. Hardie Grant Books. 2007.

Also referenced: "On Food & Cooking', The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Harold McGee. Unwin Hyman. 1984. Highly recommended for further reading on all aspects of food including its history, chemical makeup and behavior when processed and cooked.

We thank Geelong based freelance wine and food writer, Gail Thomas, for reviewing this chapter and offering her suggestions.