4.2 Attitudes Towards Wine & Food & the Birth of Self Indulgence.

|

| There are few truly great matches between wine & food, in fact several foods are completely incompatible with most wines. Artichokes contain the compound cynarin, which for most people, creates sweetness in wine where there isn't any. Oysters and cheese can cause similar clashes. When wine & food pairings are attempted, they're usually according to one of two principles: 1. Harmony; and 2. Contrast or counterpoint as represented by the two symbols above. |

4.2 Attitudes Towards Wine & Food

& the Birth of Self Indulgence.

The coupling of food with wine seems to us today to be a natural affair; both are mixtures of different chemical compounds manifested as taste, texture, aroma and flavour. More than two thousand years ago, the founder of the Western World's first culinary school expressed an elementary appreciation for the two, writing"...a fat eel is particularly good when accompanied by a good Phalernum", referring to a wine still produced in the region of Naples. However, the author, Archestratus, never actuallypromotedthe coupling of food and wine. In fact he was if anything the opposite, writing that a food of quality has"the height of pleasure within itself"needing only be seasoned with salt, olive oil and perhaps a little cumin.(1) Partly this attitude must have been due to the nature of ancient wine making - wines were not kept in barrels at that time, thus they would not have matured sufficiently to develop many of the secondary flavours conducive to pairing.

It's because culture, cuisine and wine are so closely intertwined that the practice of accompanying a specific wine with a food appeared so late in civilisation. Even in the most noble families of Europe,"...cuisine did not start to emerge from the morass of medieval cookery until the sixteenth century".Before this time,"Grand medieval meals often involved several simultaneous combinations of soup, meat, fish, poultry, and sweet dishes...a chaotic medley, [for which] matching wines would have been inutile".(2)

Long before aristocratic society began to consider the practice fashionable, we find intimate relationships between wine and food amongst the unremarkable agrarian cultures populating the wine regions of Europe. (These relationships extended not only to wine's role as the preeminent food beverage, but also to its use in food preparation as a marinade, tenderiser and enhancer of flavours)(3) From the Chateau of Bordeaux and the cellars of Burgundy, to the Bodegas of Jerez and the slopes of Germany, to the vineyards of Italy, Greece, Bulgaria and Moldavia, regional wines have being traditionally consumed with regional foods for centuries.

There were two sides to this: Where red wine was more popular or plentiful, for example, it was not uncommon to see it served with fresh seafood, without too much consideration for the character of either. ('Vin ordinaire de bouche' is a term still used by the French to describe versatile, simple wines to accompany a wide array of dishes). However, occasionally regional pairings work astonishingly well as if by some magical serendipity, 'terroir' has bestowed complementary qualities to both flora and fauna. In the Muscadet producing area of France, it's long been known that an acidic wine tastes much more delicious if the Belon oyster is dipped in a mignonette sauce of shallots and vinegar.(4)'Choucroute', a regional Alsatian dish of sausage, ham and sauerkraut works

|

| A dilemma for the 17th-century Dutch masters existed over whether to portray wine as a well-earned luxury or potentially ruinous substance. Here, a painting by Johannes Symoonisz Torrentius, Emblematic Still Life (1614), depicts a horse's harness behind a wine goblet as a symbol of restraint before indulgence. |

particularly well with the districts famous Rieslings. The simpler wines of Italy, Greece and Southern France seem uniquely suited to many garlic laced Mediterranean dishes in the same way inexpensive Chianti, Valpolicella or Montepulciano is irreplaceable next to spaghetti in red sauce and Lambrusco pairs with traditional 'zampone' in Modena or Bologna (a local specialty consisting of pigs foot stuffed with forcemeat, bacon, truffles and seasoning)(5) Whether arrived at sub-consciously or by deliberation, the food and wine synergies from these traditional wine regions mark the beginnings of reaction and honed adjustment to wine and food in combination with one another.

In certain quarters, this notion was viewed almost as a form of depravity, one which leads to idleness and gluttony and keeps people from their work, hence the emergence of convenience foods; sandwiches, smorgasbords and snacks - all easily prepared and secondary to work.

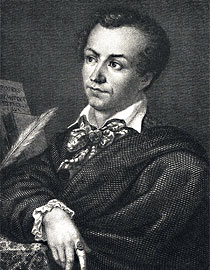

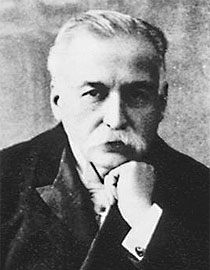

No where else were these puritanical attitudes so at odds than in France during the reigns of Louis XV and Louis XVI. Under royal patronage, culinary advances (modified over the centuries by Italians - esp. from Florence) found a heightened expression as cooking emerged from a craft and began to flourish as an art. 'Grande Cuisine' had never been 'grander.' However, the majority had never been poorer and starvation brought in the French Revolution. Thankfully, through democracy, French gastronomy lost nothing. On the contrary:"...When it ceased to be the privilege of a comparatively few extravagant idlers, it brought to the mass of the people the glad tidings that food is not to man what fodder is to his horse, merely a necessity, but that it could be and that it should be a joy as well. This happy realization came about gradually: its dawn, as brilliant and sudden as that of the tropical sun, came in during the first decade of the nineteenth century, with Careme..." (6) Still admired for greatly simplifying and codifying the style of cooking known as "haut cuisine", Marie Anton Careme (1784-1833), perhaps as a result of been brought up upon a starvation diet, was also the apostle of majesty; his dishes were nearly always richly flavoured and his cakes were works of art. Alexander I said of him'What we did not know was that he taught us to eat'.Not surprisingly, Careme is often thought of today as the first 'celebrity chef'.* Two other significant names (amongst many others who followed), are Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (1755-1826), who penned "The Physiology of Taste"(1825) and Auguste Escoffier (1846-1935), the most celebrated chef of his time and author of the magnum opus "Escoffier: The Complete Guide to the Art of Modern Cookery" (1903), a standard of classical French cooking that remains valuable to this day. (See the article "A History of Gastronomy" for more).

|

|

|

| Marie Anton Careme (1784-1833) | Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (1755-1826) | Auguste Escoffier (1846-1935) |

It was Brillat-Savarin who first coined the word "gourmandise", defining it as"a passionate reasoned and habitual preference for that which delights the palate". His family came of heroic stock and all died at the dinner table, fork in hand."Brillat's great-aunt, for example died at the age 93 while sipping a glass of old virieu, while Pierrette, his sister, two months before her hundredth birthday, uttered (at table) the following words which are forever enshrined in the memory of good French men:"Vite," she cried, "apportez-moi le dessert - je sens que je vais passer!" Yet despite his conspicuous love of food, Savarin managed to distinguish gourmandise from gluttony. In fact, he described the latter as"the enemy of excess"; while the former was"...morally...strict obedience to the creator who, having commanded us to eat in order to live, invites us with appetite, encourages us with flavour and rewards us with pleasure".To which he appended that"Alcohol is the monarch of liquids, it lifts the palate to the highest degree of exaltation; and in its various forms, has opened up new sources of pleasure...Truly matched food and drink form a civilized - perhaps indeed an artistic-creation in the world of gastronomy".(7)

Here was both an appeal to civilisation and a prophetic declaration from one of gastronomy's high priests.

What followed during the forty years from 1871 to 1910 was an enthusiastic assent as the ideas of Escoffier regarding 'Grande Cuisine' as a fine art gained the recognition and patronage of the leaders of Society both in England and in the United States, "...luxury and good taste reached in perfect harmony heights never before attained"(8). All of this was happening despite the fact that great wines and culinary prowess have never been essential to human survival. Yet the marriage of food and wine seemed to ignite the culinary imagination, beginning an adventure into chemo-sensory self-indulgence. The centuries old tradition of drinking ordinary wine with ordinary meals was giving way to a more intellectual search for interaction, compatibility of flavours, nuance and balance.

Self-indulgence has continued in some diverse and unexpected territories throughout the 20th Century. But for the most part, the traditional philosophy on food and wine pairing has remained in simpler times and foods, equating to traditional formulas such as"Red Wine goes with red meat; White Wine goes with fish and poultry" or trite recommendations like"noisettes of venison with white sauce is best served with Chardonnay 'X' ". If one's matching repertoire was to move beyond simplistic maxims some kind of extended formal training or secret initiation was required. Naturally, there were some frustrated reactions to this, one of which is a kind of 'culinary nihilism' that's still encountered today.(9)It's an unfortunate and uncoordinated attitude to wine and food, strung together by some personal idiosyncrasies and the slogan"If it feels good, then drink it" meaning: Any wine can be served with any food on desires. In reality, it's a reaction that contributes even less of value than the time honored conventional approach, and leaves two important questions unanswered:"Why do some wines work with particular foods while others don't? And "How can we define the mechanics of the food and wine pairing process?"

It was not until 1980's that two gastronomic pioneers sought to formulate self-evident concepts for food and wine matching. The book "Red Wine with Fish: the New Art of Matching Wine with Food" jolted the conventional wisdom when it burst on the scene in 1989."There are no experts on matching wine and food,"wrote co-authors David Rosengarten and Joshua Wesson, who declared that individuals can find pleasing wine and food matches by following their own palates and a few sensible principles. The authors pointed out the impossibility of harmonizing the world's myriad wines, foods and cooking styles with carved-in-stone precepts like"white wine with fish"and"red wine with meat." Those maxims appealed to previous generations seeking a semblance of order, however simplistic, in what they saw as a complex, daunting task. The duo advised readers to throw out "The Rules" and pair wine and food based on two principles:

| (a) Harmony / Similarity - whereby one tries to blend the shared characteristics into a harmonious whole, for example, a French Chablis and shellfish, a Pedro Ximenez Sherry with Chocolate cake or Christmas pudding, Amontillado Sherry and almonds (nutty & nutty), Blanc de Noirs / Rose champagne and strawberries (strawberry & strawberry) and so on. |  a. Harmony.

|

| (b) Complementary Contrasts - whereby an opposing flavour is introduced that adds a needed dimension to the food. The opposing flavours may be another food (apples and cheese, cranberry sauce with roast turkey) or a wine (roast chicken and Beaujolais or the cream and butter sauces of the Loire Valley which beg for the crisp acidity of Sancerres, Pouilly-Fumés, Vouvrays of the region). |  b. Contrast / counterpoint

|

Rather than a single perfect choice for a dish, one might find multiple pairings that were pleasing in different ways. The book was considered revolutionary at the time, encouraging open-mindedness about matching at a time when chefs were starting to look beyond European models to a more diverse global gastronomy.(10) The matchmaking practices of harmony and contrast which were considered rather tentatively in the 1980's are now generally accepted as standards in the wine and food industry today.

| The Five Possible Outcomes of Wine and Food Pairings Regardless of one's philosophy towards wine and food pairings, sooner or later we must face the fact that in the majority of considered pairings, the wine and the food won't dramatically affect each other but will 'coexist,' albeit rather unexcitingly. There are few truly extraordinary wine and food combinations, just as there are very few combinations that are truly terrible. *** In all there are five possible outcomes: 1. No match / Bad match / Clash

In the same way the some foods clash with one another, (e.g.- vanilla ice cream and anchovies) some foods contain chemical compounds that clash with wine. This fact alone immediately puts to rest the philosophy of 'anything goes with anything'. A fully ripened red wine filled with blackberry, plum, confectionery toasty oak and blackpepper flavours when paired with a slice of cucumber changes the perception of the wine instantly. Green, herbaceous cucumber flavours dominate and so the wine also tastes green and unripe. A similar clash occurs with a green capsicum. ** The technical reasons for such disharmony are partly the result of compounds in the two vegetables that, even in doses as little as parts per trillion, override the sweet berry fruit sensations of the Shiraz. Should you enjoy drinking unripe Cabernets then the capsicum would have complimented the herbaceous green flavours of the wine. The same chemical compound 2-methooxy-3-isobutylpyrazine is responsible. Certain foods are also notorious for 'tricking' our sense of taste. Artichokes contain the compound cynarin, which for most people, creates sweetness in wine where there isn't any, meaning that a tart, fresh wine like a New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc will taste unpleasantly sweet (for a few people, the cynarin reaction is reversed and makes other foods taste peculiarly bitter. Globe artichokes have been found by some to make wine taste metallic). Asparagus contains methyl mercaptan, a sulphur compound, which tends to give wine a vegetal character. Similarly, some fish, namely cod, haddock, mackerel and shellfish are high in iodine, which is why red wines don't do well with them. The iodine content reacts with the tannins in red wine and makes both the fish and the wine taste metallic. (11) 2. Refreshment Given the wildly inventive approach of many chefs and the extensive range of multicultural fare available nowadays, it's worth remembering that beverages other than wine are sometimes more suitable with certain foods. In Chinese restaurants, tea and plum wine are served with meals, in Thai restaurants, sweet tea, in Japanese restaurants, sake. Indian restaurants offer tea, beer or fruit juice cocktails while the wonderful array of beers from Belgium, Holland, Scotland & England are equally valid expressions of a relationship between food and drink. There are very few foods that destroy the appreciation of a wine, but very hot spices tend to 'stun' the mouth making it impossible to experience a wine's dimensions. Exceptionally hot dishes mean that the possibility of a good wine match is severely limited if not futile. Instead, beer or fruit juice cocktails or even water become the sensible option. Where a wine is expected, the wine itself more often than not becomes a backdrop to cleanse and cool the palate. On the whole, extremes of flavour in food tend to narrow the range of what wine pairings might work well-or at all. (See the section on Asian foods and Spices for more on this subject). 3. Neutral In certain social situations, such as a stand-up gathering with a variety of finger food, the possibility of a superior match is not only of secondary importance but almost impossible to achieve. Here, a neutral pairing of wines is desirable with wines suited to a variety of food types so that the wine and the food won't affect each other much but rather pleasantly coexist. Robust, simple wines, with strong primary fruit characters, good body and depth of flavour suffice. Such wines are immediately appealing - anything too subtle or sophisticated (or more expensive) will inevitably be wasted, not only because the pairing success will be arbitrary but because the wine will also be competing for the guest's attention in a conversational and highly distracting atmosphere. 4. Good / Adequate match This occurs when a wine complements a food's basic taste components, texture, mouthfeel and flavours as described above. 5. Sublime / Synergistic Match This equates to a match where both the best wine and food not only comprehensively complement one another, but actually enhance one another to a degree that an entirely new gastronomical effect is created. The whole becomes greater than the sum of the component parts and a leavening of the senses occurs. Such classic combinations include Sauternes and foie gras (goose or duck liver pate) or Pinot Noir and wild duck - in such examples the wine seems to melt into the food. In terms of pairing, the sublime is the ultimate objective. There will be occasions when show casing a special wine might best be matched to a simpler dish where a strongly flavoured food might completely overwhelm a fine wine, but in a truly synergistic match, the best wine and food possess a natural affinity. |

Conclusion

What are the direct relationships and reactions between the food and wine components, flavours and textures?

If we can understand the principles that govern these relationships, and allow for time and experimentation, we will be on our way to raising our culinary experiences from enjoyable to memorable, with each food and wine match in and of itself becoming a delightful experience and a stepping stone in a life long learning curve.

The next chapter attempts to explain some of these principles.

* The best known culinary writings of Careme are: Le Maitre d'hôtel Français; Le Pâtissier Royal; Le Pâtissier Pittoresque; Le Cuisinier Parisienne & L'Art de la Cuisine Français au dix-neavième siècle.

** It's even a greater injury when you're served a kebab of fine meat, skewered with green peppers and the same wine. I always take the green peppers off the skewer and drink the Shiraz with the meat, and joy - there is harmony.

*** "The only place I expect to encounter an absolutely perfect food and wine combination is in a classical three-star French restaurant. Here the menu changes only two or three times a year and part of what one is paying for is surely that the sommelier should know exactly how each dish tastes and which of the wines in his or her care - at several different price levels, please - provide a perfect match." - www.jancisrobinson.com

1. Archestratus. 'Hedypatheia' or "The Life of Luxury". Wilkins J., Harvey D. & Dobson M. (eds) Food in Antiquity, Exeter 1995). Archestratus' text is composed of sixty two extant fragments from a poem entitled "The Life of Luxury" (one of the earliest known cookbooks), from which we are able to determine what ingredients, cooking techniques and combination of flavours were preferred by the Greeks of antiquity.

(Source: Feasting with Archestratus. Kathryn Koromilas. Odyssey Journal, November/December 2007).

2. Wine Science: Principles, Practice, Perception. By Ron S. Jackson. Academic Press, 2000

3. Ibid

4. Tim Hanni, M.W., Beringer - Wine and Food Balance Program

5. As pointed out by Enrico Bazzoni in a short essay "The Italian Wine & food Perspective". From the book: Wine Pairing: A Sensory Experience. Robert J. Harrington, 2007

6. "We shall eat and drink again - a wine and food anthology". Andre Simon. 1944. Edited by Louis Golding and published by Hutchinson).

7. Writings of Brillat-Savarin include A Handbook of Gastronomy: (Physiologie Du Goût) & The Philosophy of Taste; Or, Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy.

8. We shall eat and drink again - a wine and food anthology". Andre Simon. 1944. Edited by Louis Golding and published by Hutchinson

9. Perfect Pairings. By Evan Goldstein, Joyce Esersky Goldstein. University of California Press

10. Red Wine with Fish: The New Art of Matching Wine with Food by David Rosengarten, Joshua Wesson. Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group, November 1989

11. Food & Wine, An Expert's Pairing Advice. By Ray Isle, Comments by Suzanne Yount, Mashpee Restaurant, MA

Also referenced: "On Food & Cooking', The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Harold McGee. Unwin Hyman. 1984. Highly recommended for further reading on all aspects of food including its history, chemical makeup and behavour when processed and cooked.

We thank Geelong based freelance wine and food writer, Gail Thomas, for reviewing this chapter.