2.1 Introduction to Wine making

|

| Essentially all that is needed to make wine are grapes with naturally occurring wild yeasts on the skins (to start fermentation) and a vessel, preferably one that can be readily stoppered to prevent oxidization. The vessel above is the oldest known wine jar in the world, once filled with resinated wine from the "kitchen" of a Neolithic residence at Hajji Firuz Tepe (Iran) dating to 5400-5000 B.C. Source: University of Pennsylvania Museum. |

The First Vintage.

When did humans first discover the warm rush of flavour that wine rewards? And how?

In the earliest written record of wine making the Biblical patriarch and "first vintner," Noah, is said to have planted a vineyard on Mount Ararat after the flood, later becoming drunk from the first vintage. But the fog of intoxication was no doubt thick before this time: 60 million year old fossil vines provide the earliest scientific evidence of grapes.At what point wine making began is still unknown, how it began is more easily imagined, and perhaps the most compelling illustration comes from Dr.Patrick McGovern of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archeology & Anthropology. Dr.McGovern conjures up several scenarios in his paper "The Beginnings of Wine Making and Viniculture in the Ancient Near East & Egypt":

"One can imagine a group of early humans foraging in a river valley, dense with vegetation. They are captivated by brightly coloured berries hanging in large clusters from thickets of vines and are further enticed by the tart, sugary taste of the grapes. They gather up as many berries as possible, perhaps into an animal hide or even a crudely fashioned wooden container. Some grapes rupture and exude their juice under the accumulated weight of the fruit. As the grapes are gradually eaten over the next day or two, this juice will ferment, owing to the natural yeast "bloom" on the skins, and become a low alcohol wine. Reaching the bottom of the "barrel", our imagined cave man or cave woman will sample the concoction and be pleasantly surprised by the aromatic and mildly intoxicating beverage. Additional squeezings and tastings might well ensue.

Other circumstances could have spurred on the discovery. Under the right climatic conditions, grapes will literally "ferment on the vine." The berries are attacked by moulds, which concentrate the sugar and yield a product of higher alcoholic content upon fermentation. Observant humans, such as our prehistoric ancestors must have been per force, will see various animals, especially birds, eagerly eating the grapes, followed by some uncoordinated muscular movements, and possibly will carry out experimentation of their own. The greatest obstacle in the way of substantiating a "Paleolithic hypothesis" is the improbability of finding a preserved container with intact organic material or microorganisms that can be identified as exclusively due to wine. For example, leather or wooden containers are yet to be discovered . It is possible that stone vessels or even a crevice in a rock might have been used. However, the stone vessels recovered from Paleolithic sites are not closed containers of a type that can be readily stoppered. Consequently, any Paleolithic wine made in a stone receptacle must have been produced only during [autumn] when the grapes matured, and must have been drunk quickly before it turned to vinegar.

|

| The Grapevine, Vitis vinifera vinifera, showing three varieties of the domesticated grape: blue, white, and red. Coloured engraving from Joseph Jacob Plenck (1784). |

If wine making is best understood as an intentional human activity rather than a seasonal happenstance, then the Neolithic period (8500-4000 B.C.) is the first time in human prehistory when the necessary preconditions for this momentous innovation came together. Most importantly, Neolithic communities of the ancient Near East and Egypt were permanent, year-round settlements made possible by domesticated plants and animals...

Crafts important in food preparation, storage, and serving advanced in tandem...Of special significance is the appearance of pottery vessels around 6000 B.C. The plasticity of clay made it an ideal material for forming shapes such as narrow-mouthed vats and storage jars for producing and keeping wine. After firing the clay to high temperatures, the resultant pottery is essentially indestructible, and its porous structure helps to absorb organics." (1)

A major step forward in our understanding of Neolithic wine making came from the analysis of a yellowish residue inside a jar excavated by Mary M. Voigt at the site of Hajji Firuz Tepe in the northern Zagros Mountains of Iran. The jar [pictured above], with a volume of about 9 liters (2.5 gallons) was found together with five similar jars embedded in the earthen floor along one wall of a "kitchen" of a Neolithic mud brick building, dated to ca. 5400-5000 B.C.

A serendipitous moment of fortune occurred when the jar was taken to be photographed with Dr. McGovern by the London-based Science Photo Library. Asked by the photographer to look down at the pot for the photograph, Dr. McGovern noticed a reddish residue inside the jar. Working with Museum volunteers Dr. Donald L. Glusker and Lawrence J. Exner, Dr. McGovern analyzed the absorbed material in the pottery fabric as well as the yellowish residue, using infrared spectrometry, liquid chromatography and wet chemical techniques. McGovern and his team found a combination of tartaric acid and calcium tartrate from grapes, and the yellowish oleoresin of thePistacia atlanticaDesf. terebinth tree. This resin was an additive that helped to preserve the wine and cover up any off-tastes and odours. (Modern Greek retsina wine represents a carry-over of this tradition). The research results certified the article as the world's oldest known wine jar (more than 7000 years old). It is not known whether wild grapes(Vitis vinifera sylvestris) were exploited to make the wine or if the domesticated grape (V. vinifera vinifera), from which almost all the wine in the world today is made, had already been developed.

In the aforementioned article, Dr. McGovern (et al) continues:

"Winemaking is very much constrained by the grapevine itself, even given the necessary containers and the means of preservation. The wild vine is dioecious (meaning it has unisexual flowers on separate plants that must be pollinated by insects). Only the female plant produces fruit. The wild grapevine grows today through the temperate Mediterranean basin, as well as in parts of western and central Asia. Sometime during the Neolithic Period, the wild Eurasian grapevine was eventually developed as our domesticated type. The domestic vine's advantages over the wild type can be traced to its hermaphrodism (bisexual flowers occur together in the same plant, enabling self-pollination by the wind and fruit production by every flower). Using recombinant DNA techniques, it might be possible to delimit a specific region of the world and the approximate time period when the wild grape was domesticated. A "Noah" hypothesis would seek the progenitor(s) of modern domesticated grape varieties and their sequence of development and transplantation". (2)

Aside from such possibilities, the existing evidence of our ancient past already has important implications for our understanding of the origins of viniculture (wine making) and viticulture (the cultivation of grapes), as well as for the development of modern diet, medical practices and society generally.

We have quoted Dr.McGovern here extensively by means of a prologue. But as fascinating as these diversions may be, we shall not dwell on the complete history of wine making further. That has been introduced in other articles on this site.

|

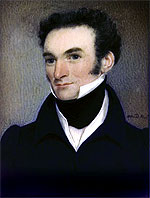

| Gregory Blaxland (1778-1853), Australia's first wine exporter. |

We jump forward in our journey several thousand years to find that wine making has become such an expansive subject, intertwined with so many disciplines that the scope of this section must remain necessarily limited to our own recent history and experience to avoid sweeping generalisations.

The Vine in Australia

To most of us one grape vine looks remarkably like another but to the vigneron the differences between them are enormous and still being calculated. Different varieties respond to different regions, different climates, different soils. Unfortunately, it is only by trial and error that these correspondences are discovered, and such trials herald the beginnings of every wine industry. In Australia, the beginnings were protracted, though not for lack of vines (cuttings were bought to Australia with the First Fleet in 1788). Rather, ignorance of viticulture amongst convicts and soldiers meant that strong spirit was the preferred palliative.

|

|

John Macarthur (1767-1834).

An early enthusiast for wine. |

Others sought to redress this. John MacArthur (pioneer and publicist of the Australian wool industry) undertook a tour of Europe in 1815-16 studying viticulture, returning with thirty vine types. Years of painstaking cultivation revealed that only six of these showed promise. In fact, much of the collection was spurious. The grape varieties, not the soil, as was previously thought, were the cause of failure. A small quantity of good wine was eventually realised from alternative cuttings, but more experiment was required.(3)

In 1816, MacArthur's unassuming success inspired Gregory Blaxland to plant a vineyard on his "Brush Farm" estate. Like MacArthur, he trialled different vine types collected en-route to Australia from the Cape of Good Hope. At that time, the Royal Society of Arts in London were offering a medal for"the finest wine of not less than twenty gallons of good marketable quality made from the produce of the vineyards of New South Wales."By March 1822, Blaxland shipped Australia's first export of wine - a barrel of claret fortified with ten percent brandy. In England, where the wine was surprisingly well received, Blaxland was awarded a Silver medal for his efforts. A second shipment in 1827 was awarded the Gold Ceres Medal of 1828 from the Royal Society of Arts. The judges stated the wine: "...had much of the odour and flavour of Claret" and that, "On tasting the samples, it was the general opinion that both of them are decidedly better than the wine for which in 1823 Mr

|

| James Busby, 1832, from a miniature oil painting by Richard Read. |

Blaxland obtained the large silver medal of the Society and that they were wholly free from the earthy flavour which unhappily characterises most of the Cape wines."Blaxland had demonstrated that with time and care, local wine could become a valuable article.

Naturally, interest in viticulture increased. James Busby left Australia for a European tour in February 1831, arriving in the Rhone Valley, France on the 10th of December. He recorded his trip in the now famous 'Journal of a Tour' (1833). Busby collected and returned with 433 varieties from the Botanic Gardens at Montpellier, 110 from the Luxembourg gardens in Paris, 44 from Sion house near Kew gardens in England and 91 from other parts of Spain and France.(4)362 cuttings were successfully grown in the Botanical Gardens of Sydney, Australia. Cuttings were subsequently distributed to Adelaide and the Hunter Valley, then throughout Australia.

However, "At this time, varieties were not well characterised and it seems certain that some were repeated...the same name may have been used for more than one variety. It is clear from the catalogue of [Busby's] collection , put out by the Sydney Botanic Gardens in 1842 that some of the varieties may also have been confused".(5)

Identifying Grape Varieties

Most of Australia's major grape varieties including Shiraz, Grenache, Cabernet Sauvignon, Mataro, Riesling & Semillon have now been correctly identified. Where incorrectly named plantings are found they can usually be recognised by ampelography and now, genetics. Ampelography involves identifying species by the shape and contours of vine leaves, the characteristics of growing shoots, shoot tips, petioles (stems that attach leaves to shoots), the sex of the flowers, the shape of the grape clusters, and the colour, size, seediness and flavour of the grapes themselves. The technique works fairly well when identifying specific varieties - that is, telling Cabernet Sauvignon from Pinot Noir. It is less reliable when telling one clone (or sub-variety) from another. Soil, climate, disease and insect damage can also alter leaf shapes, shoot growth and other characteristics, throwing ampelographers off track.

Experience in the field is perhaps an ampelographer's most valuable asset. I can recall taking two of Australia's top viticulturalists, Geoff Hardy and Ian Leask on a trip to Heathcote in Central Victoria - (Geoff is one of the 5th generation Hardy brothers.) While showing Geoff around the districts leading Shiraz vineyards I was astonished at his ability to determine vine types from several hundred metres distance, pointing out a number of Grenache vines inter-planted in a famous Shiraz vineyard, and whilst walking down a row of Shiraz vines, he could identify rogue Malbec vines. Such is his skill.

There are now thousands of recognised grape varieties with new clones constantly being developed. In their seven volume opus, "Ampelography" published in 1909, Viala and Vermorel listed 24,000 names for 5200 varieties. While Alleweldt and Dettweiler in "The Genetic Resources of Vitis" (1992) propose the existence of more than 40,000 strains, cultivars and root-stocks. Conversely, the more than 30,000 cultivars, rootstocks and vine species accounted for in literature today can probably be reduced to around 15,000 genotypes (prime names for cultivars) which include about 75 'vitis' species.

In the following chapters, we will endeavor to profile some of the most influential grape varieties grown in Australia today.

1. The Beginnings of Winemaking and Viniculture in the Ancient Near East & Egypt. Patrick E. McGovern [University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology], Ulrich Hartung, Virginia R.Badler, Donald L.Glusker & Lawrence J.Exner. (PDF article)

Note: The Origins and Ancient History of Wine, by Patrick McGovern is the first comprehensive treatment of ancient wine and is available at the University of Pennsylvania Museum Book shop: http://www.museum.upenn.edu/new/shop/m_books.shtml

2. Ibid.

3. W.M. MacArthur. Letters on the culture of the vine. Statham and Forster. Sydney. 1844.

4. James Busby. Journal of a tour. Stephens and Stokes. Sydney. 1833.

5. Wine Grape Varieties of Australia. George Kerridge and Alan Antcliff. CSIRO Australia, 1996.