New Zealand Wine: Past, Present & Future

Despite New Zealand's phenomenal success, at present it remains largely a country of boutique, quality orientated family vignerons rather than corporate giants and bulk grape growers. Most winemakers are producing a range of red and white wines and there's surprising variation between varietal styles even within regions.

Despite New Zealand's phenomenal success, at present it remains largely a country of boutique, quality orientated family vignerons rather than corporate giants and bulk grape growers. Most winemakers are producing a range of red and white wines and there's surprising variation between varietal styles even within regions.

New Zealand is still discovering itself since it has embarked on a project to classify and quantify its dizzying range of terroirs and micro climates. The array of wine styles it can potentially succeed with seems to be ever growing, including Bordeaux-style blends, cool climate Shiraz, aromatic white varietals like Gewurztraminer and Pinot Gris, not to mention its already world class Sauvignon Blanc and Pinot Noir. We trust you will find this concise introduction to New Zealand's wine regions stimulates your interest in what is one of the most exciting new wine regions in the world.

Coalescing from the Past.

New Zealand's early experiments into viticulture seem to be little more than a footnote to the staggering advances of recent decades. One finds comparisons with Italy's centuries old, now burgeoning wine industry, more so than Australia's; though admittedly, New Zealand's prolonged internal struggles to discover its latent brilliance took place within a relatively compressed time span.

What obstacles played such a drawn out role in the development of New Zealand wine?

As in Italy, an agricultural economy, poor organisation and insufficient Government support were compounded by internal disputes, foremost amongst these in New Zealand was Prohibition. Even in spite of authoritative and enthusiastic outsiders repeatedly declaring New Zealand's overwhelming viticultural potential, a crisis of self confidence in the value of its own wine industry was inevitable.

Early History

It is significant to note that the land was been trialled with vines as early as 1819 when an English missionary, Reverend Samuel Marsden, planted a vineyard in Northland. Marsden, who was no doubt preoccupied with introducing Christianity to New Zealand left no records of ever producing wine, only that"We had a small spot of land cleared and broken up in which I planted about a hundred grape vines of different kinds brought from Port Jackson. New Zealand promises to be very favourable to the vine as far as I can judge at present of the nature of the soil and climate."

|

|

| Reverend Samuel Marsden. | James Busby. |

Fifteen years later, one of the pioneers of the Australian Wine Industry, James Busby, vinified New Zealand's first wine at Waitangi, within 10km of Marsden's original property at Kerikeri. French explorer Captain Dumont d'Urville described it as"A light white wine, very sparkling and delicious to taste". Busby sold it on to British troops stationed at New Zealand's North.

The decades that followed were a typical pattern of European colonisation.

French migrants began a wine industry in Central Otago; at Nelson, German & Spanish settlers introduced commercial winemaking practices, as well as the cultivation of hops for beer production (most of the early English settlers preferred beer or spirits to wine anyway); while in Hawke's Bay, West Auckland and the Northland regions, small vineyards were planted by migrants from what's now South Western Croatia. These ' Dalmations' introduced grape varieties that produced higher quality wines, then formed a Viticultural Association. When the consumption of wine fell from over one litre per capita in 1882, to 0.74 litres in 1898, it was lobbying from such groups that lead to the establishment of New Zealand's 'Department of Agriculture' and the arrival in 1895 of one of the most influential personalities for New Zealand's early period: Romeo Alessandro Brogato (1858-1913;see below for more).

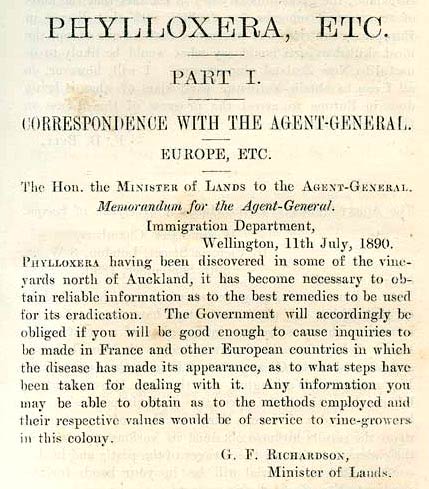

Previously a viticultural consultant to the Victorian government, Brogato travelled throughout New Zealand, evaluating and identifying every modern wine region (except Marlborough). In a report submitted to Premier Richard Seddon, Brogato praised the young industry, recommended urgent improvements (see below) and correctly predicted that the root-ruining phylloxera aphid would inevitably spread throughout the country. Gradually it did, but instead of re-grafting onto resistant rootstock, many producers turned to low-quality, but disease-resistant hybrid grapes such as Albany Surprise, Baco and Isabella. None of these would ever make great wine, yet they dominated the local industry for years.(1)At the time it didn't matter. On the whole, New Zealanders, perhaps influenced by British traditions, still preferred sweet or fortified wines which could be made from inferior hybrid varieties.

In 1901 Brogato was lured back to New Zealand to take over the Government's research vineyards at Te Kauwhata, 40 km north of Hamilton. Field days attracted winemakers keen to sample the vineyard's wines, receive advice about the best grapes for local conditions and purchase phylloxera resistant rootstock. Brogato's popular 1906 booklet"Viticulture in New Zealand" (which sold 5,000 copies) even showed vignerons how to successfully graft their existing vines onto American rootstock.

Romeo Bragato: Romeo Bragato: Father of the New Zealand Wine Industry. On the 19th February 1895, Romeo Bragato arrived at Bluff on loan from the Victorian Government to the Department of Agriculture. He came with impressive credentials, having spent four years at Conegliano, Italy's famous school of viticulture where he obtained a diploma of Oenology. He was escorted by Government officials from one end of the country to the other. His report, 'Prospects of Viticulture and Instructions for Planting and Pruning' submitted to the premier on 10th September the same year was reasoned and enthusiastic. Bragato strongly urged that associations be formed in the various districts, "A competent body in each district would determine the most suitable varieties for planting, collect and spread local data and thus in great measure secure the industry against failure. Each district would subsequently gain notoriety for the wine produced as in the famous districts of the Continent". He had found phylloxera in the Auckland vineyards of Mr Bridgman and Mr Harding of Mt Eden Road and strongly recommended an inspection of all vineyards. He also recommended the importation by the Department, from Europe, of cuttings of American resistant vines. Signor Bragato returned to Australia, leaving behind him a farming population excited by the prospects of wealth from viticulture. But two pests, Phylloxera and Oidium Mildew, and a lacklustre policy by the Department of Agriculture dampened the enthusiasm of most except the wealthy gentlemen farmers of Hawke's Bay, the missionaries, and a new breed of wine growers entering the field, the Dalmatians.  Enquiry about phylloxera control, 1890. Phylloxera was first reported in New Zealand in 1885, but the insect's identity was not confirmed. After it was discovered in some Whangarei vineyards in 1890, the minister of lands requested information from French and other European governments about the methods they had used to deal with phylloxera.Bragato imported disease resistant stocks and in his handbook, Viticulture in New Zealand published in 1906 by the Department of Agriculture, showed growers how to graft the European classical varieties which predominated in the country at that time, on to the American root stocks. Bragato's work identified the varieties to plant, the Phylloxera resistant rootstocks to graft them to, the regions in which to plant vines, the varieties suitable to each region, vineyard layout, pruning methods and much more. Regrettably his work was not acted on and lay forgotten for over 60 years. Dusted off by a few pioneers in the 1970's early 1980's, many of the recommendations of Romeo Bragato form the basis of modern New Zealand viticulture practices. (8) |

New Zealand's Romeo Bragato Conference, Bragato Address, and Bragato Wine Awards salute the vision of Bragato.