Spanish Sherry

Introduction

Introduction

Jerez, the home of Sherry in Southern Spain, has exported wines since at least Roman times and today its wines account for the greatest volume of any Spanish 'Denomination of Origin' exports. They are sold in over fifty countries. The enormous international success of these wines is, to a large degree, due to the long export tradition, the broad consumer range and the wine's exceptional quality, which has its source in the regions unique winemaking and ageing processes.

In Australia, Sherry has become somewhat unfashionable, being considered a drink for social matrons and the elderly. This attitude is slowly changing as wine-lovers are discovering the wonderfully different taste experience Sherry offers. As well as being an incredibly versatile drink, Sherry wines generally deliver remarkable value for money, with some examples sitting comfortably alongside the great wines of the world.

The past few years have witnessed a widening range of Sherry wines on the Australian market and, thanks to the meticulous work of the winemakers and the initiatives undertaken by the Jerez Regulatory Council, a small amount of exceptionally rare and old Sherry is also being released to the public. Nicks Wine Merchants have recently imported some extraordinary examples of these world treasures including Amontillado, Oloroso, Palo Cortado and Pedro Ximenez wines aged more than twenty and thirty years. Also imported are younger Pedro Ximenez (one of the great sweet wines of the world), and Manzanilla Sherry. Both wonderful flavour experiences.

This article offers a comprehensive account of the Jerez region, from its history to the architecture of its Bodegas, and of course a detailed introduction to the drink that has made Spain famous. Much of the information has been supplied by the official Spanish Sherry Organisation so offering a first hand description of the viticulture, viniculture and enjoyment of this unique drink.

The Origins of Sherry Wine

The Origins of Sherry Wine

The most ancient mention of Sherry comes from Strabo, the 1st-Century B.C Greek geographer. In his book Geography (vol. III) he wrote that the first vines were brought to the Jerez Region by the Phoenicians in 1100 B.C. Archaeologists have recently discovered two winepresses in the excavation of an 4th-Century B.C. Phoenician site, in Castillo de Dona Blanca, just 4 km from Jerez de la Frontera [pictured right]. This discovery confirms that the same people who founded Gades, or Cadiz, brought the art of growing vines and making wines from the far-off lands of Lebanon to Europe & Spain. In Xera, the Phonecian name for the region where the modern city of Jerez in Spain is now located, this trading nation produced wines which were then exported to the whole of the Mediterranean Basin, especially Rome.

The Greeks and Carthaginians also made important contributions to the region's history. Around the year 138 B.C. Scipio Aemillianus pacified the Betica region, establishing Roman rule and opening up a very substantial trade flow of products from this area toward the metropolis. The people of Cadiz exported to Rome olive oil & wine from the Region of Ceret as well as garum, a kind of marinade sauce that was prepared from the leftovers of the fish that they salted. Even by then, the fame of "Vinum Ceretensis" had already crossed our frontiers and was not only appreciated in Rome, but also in many other parts of the Empire, something proven by many archaeological remains, in the shape of amphorae bearing a stamp in their clay according to their content (for tax purposes).

The Land of Sherish

In 711 AD the Moorish occupation of Spain began, opening a period of history which in the case of Jerez was to last more than five centuries. During this time, Jerez remained a large wine-producing centre in spite of the Koran's prohibition. The production of raisins and the distilling of alcohol for medical purposes (for which even the Moors drank Sherry) were to a certain extent, pretexts for maintaining vine cultivation and wine production.

However in 966, Caliph Al-Haken II, an extraordinarily cultured monarch who founded a 400.000-volume library in his Cardoba palace and made education compulsory for all children in Andalusia, ordered the grubbing-up (up-rooting) of the Jerez vineyards on religious grounds. In his defence it must be said that this "lapse" of grubbing up the vineyards was not his own idea, but that of Al-Mansur, his vizier. Al-Mansur was an unbelieving Arab, yet curiously enough some of his surviving poetry is in praise of wine. The people of Jerez replied to Al-Haken that the grapes were used to produce raisins to feed the troops in their Holy War, which indeed was partly true, thus ensuring that only one third of the vineyards were destroyed.

A map of the region dating from 1150 is kept in Oxford University's Bodleian Library, drawn up by the Arab geographer Al-Idrisi for King Roger II of Sicily. A curious feature of the map is that the North is at the foot of the page and the South at the top. The map clearly shows the Arab name, - Seris (pronounced Sherish). The Arab name then is the origin of the English word, Sherry and the Spanish "Xerez". This map later re-appeared in History for a different purpose - settling the first lawsuit brought by the Jerez producers against what was called British Sherry (1967). It served as a key piece of evidence of the improper use of the Sherry Denomination of Origin, proving that the word "Sherry", used to denominate Sherry throughout English-speaking world, is clearly derived from the city of Jerez's former name.

A map of the region dating from 1150 is kept in Oxford University's Bodleian Library, drawn up by the Arab geographer Al-Idrisi for King Roger II of Sicily. A curious feature of the map is that the North is at the foot of the page and the South at the top. The map clearly shows the Arab name, - Seris (pronounced Sherish). The Arab name then is the origin of the English word, Sherry and the Spanish "Xerez". This map later re-appeared in History for a different purpose - settling the first lawsuit brought by the Jerez producers against what was called British Sherry (1967). It served as a key piece of evidence of the improper use of the Sherry Denomination of Origin, proving that the word "Sherry", used to denominate Sherry throughout English-speaking world, is clearly derived from the city of Jerez's former name.

Wine after the "Reconquista"

The conquest of the city of Jerez by King Alphonse X ("The Wise") in 1264 brought a 180º turn around for the wines of Jerez. The King himself had vineyards in Jerez and he took a personal interest in their care. For two and a half centuries after its Reconquest from the Moors, the town of Xeres (Jerez), along with other nearby towns and cities , marked the limits of the Kingdom of Castile and thus received the name "Jerez de la Frontera" (Jerez on the Frontier).

During that period and even in the 12th Century, wines from Jerez were exported to England where they were known by an anglicised version of the city's Arab name "Sherish". As a fortified wine, sherry was better equipped than most table wines to survive the sea journey to the British Isles, and it was prized there. The wines became especially popular in England when Henry I, in order to develop the produce of both countries, proposed a bartering agreement to the people of Jerez: English wool for Sherry Wine. From that moment, the Jerez vineyards became an important source of wealth for the kingdom, to such an extent that King Henry III of Castile prohibited by Royal Order the up-rooting of even a single vine also forbidding the placing of beehives near the vineyards to prevent the grapes being damaged by bees.

From that moment, the Jerez vineyards became an important source of wealth for the kingdom, to such an extent that King Henry III of Castile prohibited by Royal Order the up-rooting of even a single vine also forbidding the placing of beehives near the vineyards to prevent the grapes being damaged by bees.

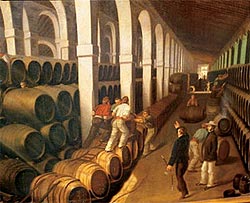

The growth in demand for Sherry Wines by English, French and Flemish merchants led to the Jerez city government's proclamation of the Rules of the Guild of Raisin and Grape Harvesters of Jerez on August 12th 1483. These were first rules of Jerez's Denomination of Origin and regulated the details concerning harvesting, the characteristics of the butts (known as botas), the ageing system and commercial procedures for the production of Sherry.

The Modern Age; Expansion Overseas.

The Modern Age; Expansion Overseas.

The discovery of America would lead to the opening of new markets; the Sherry trade flourished. This was the period of epic voyages and geographical discovery - a series of events celebrated with sherry wine, exemplified by explorer Ferdinand Magellan who in 1519 purchased 417 wineskins and 253 kegs of Sherry before setting out on his voyage, spending more on Sherry than weapons. Sherry, therefore, was the first wine to make a complete trip around the world assuming of course, there was any left when the Nao Victoria returned to Sanlucar under the command of Juan Sebastian Elcano!

Trade with the Indies turned small family wine businesses into truly international operations. Many "naturalised" Italians who settled in the region, such as the Lilas, Maldonados, Spanolas, Contis, Colartes and the Bozzanos, contributed to this growth. Wine enjoyed the privilege of being allocated one third of the cargo space reserved for it on the ships that traded with the Americas, something that the Jerez winegrowers took full advantage of, especially from 1680 onwards when Cadiz became home port to the Americas fleet and Seville lost its monopoly of trade with the Indies.

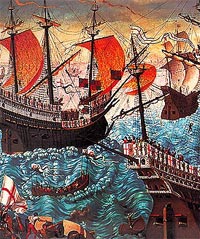

However, the sale of Sherry in the Indies was hampered by pirates who seized the fleet's cargoes, selling them back to London. But the greatest haul of Sherry wine was made in 1587 when the English

attacked Cadiz and carried off 3,000 kegs. When this booty arrived in London, Sherry became fashionable in the English Court. Elizabeth I herself recommended it to the Count of Essex as the best of wines. With a rapidly increasing trend in the consumption of Sherry, and faced with a scarce supply, James I of England decided to set an example by ordering that the Royal Cellars should only bring to his table 12 gallons (48 litres!) of Sherry per day.

Some picture of the popularity of Sherry at that time can be gained from the works of William Shakespeare, who in the company of his friend Ben Johnson at the Bear's Head Tavern used to drink a good few bottles every day. The Bard refers to it frequently in many of his plays; Richard II, Henry VI, A Midsummer Night's Dream, The Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry IV, amongst others. Shakespeare's character Falstaff was an ardent fan of the beverage (then known as sack), proclaiming:

Some picture of the popularity of Sherry at that time can be gained from the works of William Shakespeare, who in the company of his friend Ben Johnson at the Bear's Head Tavern used to drink a good few bottles every day. The Bard refers to it frequently in many of his plays; Richard II, Henry VI, A Midsummer Night's Dream, The Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry IV, amongst others. Shakespeare's character Falstaff was an ardent fan of the beverage (then known as sack), proclaiming:

"If I had a thousand sons, the first humane principle I would teach them should be, to forswear thin potations and to addict themselves to sack". ("Sack" being an old term for Sherry).

As demand for Sherry rose the English decided to obtain the wines by fair means or foul. In 1625 Lord Wimbledon attempted a new attack on Cadiz but was unsuccessful. It was probably this failure that led the English (and Scots and Irish) to assure their supplies of Sherry through the usual trading channels, establishing their own businesses in the Region. The 17th and 18th Centuries saw the arrival of wine merchants such as Fitz-Gerald, O'Neal, Garvey and MacKenzie. Later they were followed by Wisdom, Warter, Williams and Sandeman. Being British subjects, some Jerez wine-growers were able to bring pressure to bear on the British government in order to lower the excise duty, achieving their objective in 1825 with a reduction of two "duros" (a Spanish monetary unit) per bottle. This led to a four-fold rise in the sales of Sherry between 1825 and 1840.

As demand for Sherry rose the English decided to obtain the wines by fair means or foul. In 1625 Lord Wimbledon attempted a new attack on Cadiz but was unsuccessful. It was probably this failure that led the English (and Scots and Irish) to assure their supplies of Sherry through the usual trading channels, establishing their own businesses in the Region. The 17th and 18th Centuries saw the arrival of wine merchants such as Fitz-Gerald, O'Neal, Garvey and MacKenzie. Later they were followed by Wisdom, Warter, Williams and Sandeman. Being British subjects, some Jerez wine-growers were able to bring pressure to bear on the British government in order to lower the excise duty, achieving their objective in 1825 with a reduction of two "duros" (a Spanish monetary unit) per bottle. This led to a four-fold rise in the sales of Sherry between 1825 and 1840.

Investing in the region was a profitable business and it attracted substantial Spanish capital, especially the so-called "returning capitals", flowing back into Spain after the de-colonisation of American possessions. This period saw the arrival of the Gonzalez family (1835), the Misa family (1844) and a numerous group of Basques: Goytia, Muriel, Otaolaurruchi, etc. However, the commercial boom in the 19th Century would not have been possible without the previous existence of a series of favourable conditions. Ironically, this was also the period during which phylloxera ravaged the vineyards of Europe and many bodegas went bankrupt before replanting was achieved in the 20th century. Nevertheless, recovery was particularly quick, as the means to defeat phylloxera were already well known by the time it reached the region.

The 19th century; Sherry as we know it today.

After a long, turbulent history, the late 18th-Century wines from the Jerez Region were still a far cry from the wines that we now recognise as Sherry. At that time the struggle between the winegrowers (productores) and merchants (extractores) was clearly being won by the former.

The rules of the Vintners' Guild, dominated by the winegrowers, expressly prohibited the storing of wines of different vintages, considering it a "speculative" practice. As a result, the wines exported were always young wines from that year's harvest, highly fortified in order to preserve them during their long voyage. 1775 was the year when the so-called "extractors' action" began. It lasted for decades until the Guild's restrictive trading rules were definitively abolished, allowing for a more effeicient commercialisation of Sherry wines.

The possibility of storing wines from different harvests and the need to supply the market with a product of a consistent quality gave birth to one of the fundamental contributions of Jerez to the history of wine: the ageing method known as "Criaderas y Solera" (more on this later).

In addition to this, as the wine reposed longer in barrels, the addition of grape distillate changed from being a method of stabilising the wines into a true enological technique, which when added in different quantities, led to the creation of the wide range of Sherry wines available today.

Between 1944 and 1979 Sherry exports rose dramatically from 135,000 to 1,500,000 hl. However, in the 1980s they fell by 50%. Today, exports have stabilised at the 700-750,000 hectolitre mark, but the total value of the wines is much higher than in 1979.