Ingredients: The Fruits

The fruit liqueurs, in the opinion of most people probably, are the easiest to get to know. When he comes to deal with fruits, the Liqueurist will always strive to bring to the surface, or the forefront as it were, the very best and most admirable properties and qualities of a single fruit. He will want to show his cherries, say, in their best possible aspect and thus any additional flavours he may add, in the way of herbs or spices, will be in a minor role so as not to detract from the full beauty of colour, bouquet and flavour of the central fruit.

Allow me for a moment to digress at this point and talk about taste. Everyone knows what the word means-, it is that quality or property of a substance which is perceived when it is brought into contact with the tongue and other portions of the mouth. It is also of course the same word we use to name the human faculty or sense by which that quality or property, as just mentioned, is detected. There are four broad kinds of taste which we can detect and isolate. These are sweet, bitter, sour and salty. Sugar has a sweet taste, apricot kernels or apple seeds have a bitter taste; lemons and unripe fruit have a sour taste. Liqueurs and fruit liqueurs in particular bring our taste buds into full operation and require us to make immediate and extremely accurate decisions as to how much there is of each taste factor in the liqueur we are tasting. Thank heavens our nearinstantaneous computer in the brain allows us to come up with a split second judgment, that we like or dislike what is in our mouth. What we are doing is judging whether the three factors are in balance or not and if one taste, say acid sourness, predominates whether this is agreeable to us. (I have not dealt with saltiness as this has very little application to liqueurs. Salt can, however, have a counteracting and balancing effect on sourness. Tomatoes taste quite different unsalted.)

In my words on taste you will notice I have refrained from mentioning flavour. This is quite separate from taste but can only be measured in conjunction with it. It is the element in the taste which depends on the co-operation of the sense of smell for its detection. Without our sense of smell we are quite unable to properly "taste" anything. With this digression then in mind we can proceed to talk about the fruit liqueurs. In any discussion of these, however, there is frequently an area of dispute over the application of the word "brandy" which it is best to clear right from the outset.

Fruit brandies are one thing and fruit liqueurs, albeit with brandy in their name, are quite another. Fruit brandies are chiefly produced in Europe where the fresh fruit for their production is available in large quantities. They are the product resulting from the distillation of a "wine" made from the fermented juice of a fruit other than grapes. (If it were from grapes it would be the grape brandy we know and make here.) So we find that when apple juice is fermented into cider and this is distilled, Apple Brandy or Calvados or Applejack is the resulting spirit. Similarly, fermented and distilled plum juice gives us, depending on the country of origin and the variety of plums used, Slivovitz, Quetsch or Mirabelle. From cherries we get Kirsch or Kirschwasser; from strawberries, Eau de Vie de Fraises and so on. The Germans do this nicely. When they make strawberry brandy they call it Erdbeergeist; literally Earth- berry-ghost. Everyone understands that a ghost is a spirit! These are all high strength spirits, unsweetened and water-white when they come from the still. Mostly they are kept this way by maturing them in stoneware or glass-lined vessels so they do not pick up any colour from wooden casks. They retain a very definite and delicious real-fruit indication on the nose. But you can readily understand why they are so expensive. I should think that a strawberry brandy made here from fruit costing 50c per punnet could cost about $20.00 per bottle without any duty.

But these are the fruit brandies, and beautiful they are. Fruit liqueurs though are spirits, which may be from any source but are frequently grape brandies, flavoured with fruit and sweetened with sugar syrup or honey. They are broadly in three categories: those made from stone fruits, those from citrus fruits, and those from soft fruits.

Stone fruit liqueurs often have brandy in their name, Cherry Brandy, Apricot Brandy for instance, and in these cases the base spirit is always fine brandy made from grapes. In making these liqueurs the pulped fruit is macerated with the spirit for some days or weeks. It is usual to include the kernels of the fruits in the macerate so as to give a slightly bitter tang to the final product. Apricots, peaches and cherries are used in this way in many parts of the world. Sometimes herbs are used to enliven the fruit flavour and spirits other than brandy are employed. The Scots, predictably, have a whisky flavoured with black cherries and herbs called Gean Whisky. Peter Heering make an excellent cherry liqueur from their own cherry orchards near Copenhagen. Others come from Italy (Cerasella), Venezuela (Ponsigue), Finland (Sorbino), Uruguay (Guindado) and of course from France where Rocher Freres and Marie Brizard have their headquarters making beautiful products from their locally available raw materials.

An interesting sidelight to cherry brandy making in France is that before pulping, the stems must be removed from the fruit, a tedious and costly business in itself but were this not done the liqueur would be coarse and hard due to the excess of tannin. A part of the cost of this removal is, or used to be, recovered by selling the cherry stalks to herbalists and druggists. An idea of the French trade in cherry brandy may be gathered from the knowledge that certain manufacturers used to sell up to a ton and a half of stems annually! Now cherries (Prunus avium and Prunus cerasus), peaches (Prunus Persica) and apricots (Prunus armenica) are all originally from Western Asia or China and, while they are cultivated in all parts of the world today, they still- grow best in these places and Europe. Unfortunately our cherries in Australia, while they look superb and taste quite good when eaten fresh, do not make good liqueurs. They lack the wonderful fruit acids and excellent flavour characteristics of the Northern hemisphere fruit with the result that we have to import cherry fruit -concentrate from our various supplying countries and reconstitute it in Australia, no small feat to do well.

Before leaving the stone fruits I must speak of Maraschino. Originally made from the exceptionally sour Marasca cherry grown only in Dalmatia (now Jugoslavia) it is now made in Italy and elsewhere including Australia. It still relies for its flavour on the marasca cherry which is enhanced with the essence of orange flowers plus walnut and orange oils. It is a truly lovely liqueur with great delicacy of fruit and a floral bouquet.

Citrus Fruits are the next group and these are very largely based on oranges of which the best known is the Curacao orange. In most cases the flavouring is derived from the aromatic essential oils contained in the peel. The island of Curacao, a former Dutch Colony to the north of Venezuela, still produces peel today which is used fresh on the island as well as being dried for export. We use some peel from Curacao and some from the West Indies. The oils are extracted by soaking the peel in water then steeping in spirit and finally by distillation. The distillate may be used as is, by merely sweetening, or it can be further reduced to its essential oil components. These can then be compounded into a liqueur. The Curacao liqueurs differ greatly, not only in colour from water white, through red-gold to blue, but also in their flavours from extremely dry and very strong to quite heavy and sweet with a note of rum in the background.

And finally in the citrus area I must mention in passing the Cumquat. This tiny orange, grown in many home gardens for its pleasing appearance as well as its fruit, is often preserved in sugar and brandy to give a rough home-made liqueur. I hope I will not be accused of sour grapes (or sour cumquats) if I say I do not usually enjoy these home-made eff orts; the acid is too raw and strong for my palate and there is a lack of balance and finesse. Usually, also the colour and condition often leave much to be desired. But their owners love them so who am I to say!

Lastly in this section are the soft fruits. Strawberries. raspberries, blackberries, black and red currants. pears, apples and quinces are the soft fruits of France and Europe. In the New World they extend to bananas, pineapple and passionfruit. I do not intend to go through the extractive procedure again: you know that now. Because these fruits are all so soft in both texture and acid, their beautiful juices are immediately and readily available to the liqueurist who really only needs to exercise care and caution and use the best selected base spirit so he will not damage or harm the flavours within his grasp.

"Creme de Cassis" or Blackcurrant Liqueur is one of the best known soft fruit liqueurs and has been made for centuries throughout Europe. Monks in the 16th Century were making it in the Dijon area of South-east France where high quality blackcurrants still form a second cash crop amongst the vines of Burgundy. And we are extremely fortunate in that Tasmania produces truly excellent fruit with beautiful colour and deep intense flavour. In fact you will see from the map in pages 16 and 17 it is one of very few natural ingredients we obtain from our own shores.

"Blackberry Liqueur" is made particularly well in Germany and Poland where the fruit is of a much higher quality, being higher in fruit acid and flavour characteristics than that obtained from the proclaimed noxious weed which plagues our farmers in this country.

Sloe Gin is a very old liqueur which employs sloe berries, the fruit of the blackthorn bush, a type of plum, steeped in gin and sweetened to a degree to give a delightful rich deep-red coloured liqueur somewhat astringent and traditionally served as a stirrup cup at the commencement of the Fox Hunt.

It may only be of academic interest to my Australian readers, but I cannot fail to mention the mind-catching liqueurs from Finland. This land which enjoys (or othenwise) sunlight till midnight for months of the year. being within the Arctic Circle, has fruits we do not encounter with any dependability elsewhere and the Finnish liqueurists use them to wonderful effect. They are all varieties of the Rubus species, cranberries, cloudberries and brambles, and are close relatives of blackberries. The expressed juice is ruby-red in colour. They grow wild in the boggy Finnish marshland where the pickers must compete with the wild bears for the harvest.

Pineapples and bananas give rise to liqueurs in Hawaii and Australia, and of course in other parts of the world also, called respectively by their French titles, Creme d'Ananas and Creme de Bananes. To date they have not greatly caught the consuming public's imagination, perhaps because although they are redolent of fruit they are somewhat too bland and ethereal. They have been criticized by many as having too artificial a flavour even when made by a true and authentic extractive process from the natural fruit. This point leads me into another and that is artificial flavourings.

As any tyro learning the science of organic chemistry will tell you, it is remarkably easy to produce in a test-tube a clear colourless liquid which has, very dramatically, both the smell and flavour of a naturally occurring substance. For example, if we take a small quantity of ethyl alcohol which has almost no odour or flavour, and add to it some acetic acid, the acid which is basically vinegar, we obtain immediately one of the simple esters. Ethyl acetate, which smells strongly of rum. Similarly, if acetic acid is added to Amyl alcohol we obtain Amyl acetate which is Bananas, Bananas, all the way! Now let us be quite clear on this point. A careful analysis of the flavour compounds of real bananas would show that various "aromatic" organic compounds were present and these would include Amyl acetate together with a host of others.

In the picture at the top of this page you will see fruit samples ready for testing and extracted juices prepared for tasting and blending in our laboratory. It may be you will not like all of our liqueurs but of one thing you can be sure: they have all been prepared with the most painstaking care using only the finest and purest of ingredients we can obtain against long developed formulae which, incidentally, are approved by the Australian Government Analyst. We may not vary or depart from these recipes without advising him and obtaining his approval for the change. Liqueur making is not easy, but we love doing it.

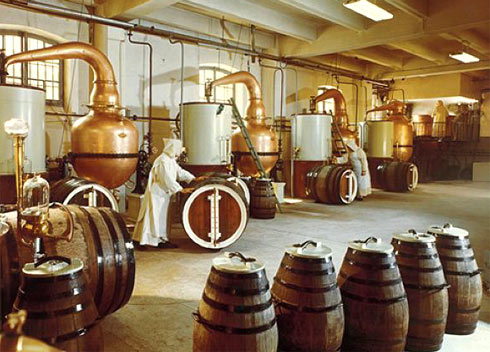

Extraction of Fruits

We show two Fruit processes -

Firstly: Citrus oil extraction from peel. Secondly: Maceration of Soft Fruit.

Citrus Oil Extraction from Peel

COLD PRESSING. Much of the flavour in citrus fruit is contained in the oil of the peel. The peel is reamed, scraped or cold pressed by tiny sharp steel spikes or screws which rupture the cells and release the essential oil. Water is sprayed through the press to wash the oil away from the peel. An alternative method used for Curacao peel is to soak or macerate the peel in alcohol for many weeks to extract the oil.

ESSENTIAL OIL SEPARATION. The water and essential flavour oil is left to stand and separate in a glass vessel. The essential oil gradually floats to the top as it is lighter than water. Approximately 1,000 kilograms of peel will yield 4-5 kilograms of Essential Oil.

FIRST RECTIFICATION. The essential oil is now rectified in a fractionating column. This is a redistillation process to ensure that only the purest, cleanest and most prized oils are selected and concentrated This process allows the unwanted fractions to be separated and removed. The yield of high grade oil is now down to 100 grams per 1000 kilos of peel.

SECOND RECTIFICATION. This final process, when used, further refines the oil and gives a concentrate which contains over 95% of the flavour of the original peel.

Maceration of Soft Fruit

MACERATION. This process is used particularly for stone and soft fruits-, cherries, apricots, peaches and blackcurrants. The pulped fruit, usually including the kernels, is soaked in alcohol for several days or weeks, depending on the particular fruit and the strength of flavour required.

SCREENING AND FILTERING. The Macerate is screened and filtered to remove the flesh, peel and fruit cells as these now contain little flavour and would make the liqueur cloudy. What remains after filtering is a mixture of juice, with all its flavouring compounds, and alcohol.

VACUUM DISTILLATION. The mixture is placed in a still where the alcohol is evaporated off leaving the concentrated flavour. This is done under vacuum and reduced temperature as heat could damage the flavour.